Scotch Heart

Tuesday, March 22, 2011 at 11:33AM

Tuesday, March 22, 2011 at 11:33AM  David Shepherd,

David Shepherd,  Film,

Film,  Music,

Music,  Quiet

Quiet  Tuesday, March 22, 2011 at 11:33AM

Tuesday, March 22, 2011 at 11:33AM  Share Article

Share Article  David Shepherd,

David Shepherd,  Film,

Film,  Music,

Music,  Quiet

Quiet  Tuesday, March 1, 2011 at 8:47AM

Tuesday, March 1, 2011 at 8:47AM

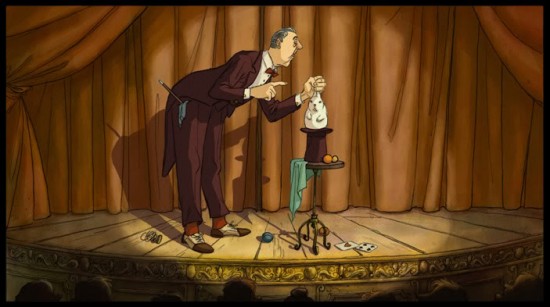

There are actors and actresses who do not need to speak a single word to convey meaning and emotion. As masters of their craft, a raised eyebrow, shifting of balance, or gesture of the hand speaks volumes and such is the animation of Sylvain Chomet.

Chomet first rose to prominence with his 2003 film, Les Triplettes De Belleville, a highly stylized, comic period piece acclaimed for it's eye-catching, traditionally styled animation, quirky characters, and lively musical score. The film contains almost no actual dialogue, and the genius of Chomet is that it is hardly even missed. Through the use of facial expressions and overblown gestures, Chomet creates a sort of animated mime that speaks far more than words ever could - a technique that serves him particularly well in his second full-length film, L'Illusionniste.

Based on a script by Jacques Tati, a French comic actor and director who himself began as a mime, L'Illusionniste tells the story of a travelling magician in the dying days of vaudeville-style theatre. The magician (based on Tati himself), carries about him an air of dignity and quiet resignation as he moves from town to town performing for dwindling crowds. A scene where he repeatedly goes through a complex series of preparations in anticipation of stepping on stage only to be rebuffed by a young rock band's repeated encores offers a quiet sense of pathos and the world moving on. After taking an engagement in a remote Scottish village, he meets a young girl who he delights with a few of his tricks. They form a connection which leads them to Edinburgh where they both attempt to build new lives as surrogate father and daughter.

The colours and style are more muted than the exuberance of Triplettes, as befits the more somber story, but Chomet's sense of wonder, conveyed through the exquisite detail of Edinburgh's streets, the Scottish countryside, and even the dingy theatre backstages, still shines through even as his playfulness is evidenced in characters like his three tumbling brothers, the magician's surly rabbit, and a cameo from Triplettes' buck-toothed, mouse-like mechanic. The sedate pace and subdued mood create an atmosphere where the merest of movements and smallest of gestures convey great meaning and a bowl of soup can stop a suicide and a gift of new pair of shoes begins the transformation of two lives.

With it's recent Oscar nomination, L'Illusionniste has been seeing some wider distribution, and I highly recommend catching it on the big screen if you can. It's traditional, hand-drawn animation and quiet beauty are a refreshing respite from the flash-bang of 3D digital images and well worth the investment of your time.

Share Article

Share Article  Animation,

Animation,  David Shepherd,

David Shepherd,  Film

Film  Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 11:52AM

Thursday, January 13, 2011 at 11:52AM The making of things can be a tricky business, particularly in the arts. Birthing a vision relies on a myriad of tiny steps which, when executed correctly, add up to a glorious whole. Support must be rallied, resources put in place, collaborators found, experts hired, and schedules arranged. It's a careful dance between chaos and order that can lead to great things, but when fate sticks out it's foot and trips up momentum, it can bring the whole works to a shuddering halt.

In September of 2000, acclaimed director Terry Gilliam (Brazil, 12 Monkeys, Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas) was ready to begin filming his long-dreamed adaptation of Don Quixote. The actors were hired, the sets prepared, the costumes sewn, the storyboards drawn, and independent financing was fully secured. Along for the ride were documentary film-makers Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe, chronicling both the giddy anticipation as pieces fall into place, and the careful dance of negotiating the obstacles that arise. The excitement, however, quickly gives way to a mounting despair as a flash flood wipes out equipment and sets, the lead actor falls seriously ill, and the ensuing delays threaten to derail the film completely. Fulton and Pepe are there for it all, capturing the footage they eventually assembled into Lost In La Mancha - a film they came to call a documentary of the "unmaking of" a film.

Share Article

Share Article  David Shepherd,

David Shepherd,  Film

Film  Friday, October 22, 2010 at 10:16AM

Friday, October 22, 2010 at 10:16AM I enjoyed reading David Beronä’s book, Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (2008), which describes (with select examples) the work of early-20th century woodcut storytellers such as Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward. Beronä makes glancing suggestions that these initially small publications (descended from block-books and playing cards) are the missing link between the cinema and modern day graphic novels. “When Thomas Mann,” he writes, “winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929, was asked what movie had made the greatest impression on him, Mann replied, ‘Passionate Journey.’ Although Mann’s reply sounds like the title of a film by D. W. Griffith, it was, in fact, a novel in woodcuts by Frans Masereel.”

Beronä contends that the prevalence of German expressionist woodcuts, the popularity of silent film (in particular its heroes like Chaplin, and visual achievements like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Last Laugh), and the rise of political cartoons in newspapers set the stage for the woodcut novel. Beronä writes: “For a public already familiar with black-and-white pictures that told a story, worldess books offered the public, in one sense, silent cinema in a portable book that they could ‘watch’ at their leisure.”

Fittingly, the German publisher of Masereel’s 1920 The Idea (83 woodcuts visualizing an idea as a naked woman enraging elites but inspiring the masses) commissioned an animated adaptation. He turned to Berthold Bartosch, the Czech-born Berlin filmmaker who created many of the atmospheric effects in the world’s first animated feature, Lotte Reiniger’s brilliant The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Bartosch was not only a perfect artistic and technical choice, like Masereel (who was a member of the Red Cross and the international pacifist movement during World War I) he was a leftist who counted among his friends Reiniger, Carl Koch, Jean Tedesco, and Jean Renoir.

Bartosch emigrated to Paris in 1930, where he created his 25-minute adaptation, also entitled The Idea (1932), which his future friend and colleague (and brilliant animator in his own right) Alexander Alexieiff called “the first serious, poetic, tragic work in animation.” (The film is also noted for Arthur Honegger’s score, which is thought to be the first to utilize an electronic instrument, the ondes Martenot.) Alexieiff’s statement is no hyperbole: Bartosch’s film, with its adagio pacing, multiple layers of foggy (actually soapy) luminescence, and evocative urban detail, is a stunning achievement even today. Not content with simply animating the woodcuts (even if that were possible), Bartosch constructed an original vision that draws directly from Masereel’s imagery but re-envisions it as moving graphic illustrations extracted into deep space, its detailed cityscapes, swirling atmosphere, and dramatic superimpositions fusing together fantasy and reality. Appropriately for a film based on a “worldless book,” Bartosch shuns the use of intertitles except for a brief prologue extolling the durability of ideas.

From 1935 to ‘39, Bartosch worked on an epic anti-war film, but according to Robert Russett and Cecile Starr (who shares the copyright with Bartosch’s widow on The Idea’s 1976 print) in their seminal book, Experimental Animation, “about 2,000 feet of film had been shot when Bartosch and his wife were forced to flee Paris at the time of the Nazi occupation. All negative and positive material of the uncut film was deposited in a vault of the Cinémathèque Française; none of it was found again. Only a few test strips were saved…”

Alexeieff picks up the story in an interview reprinted in the book:

* * * *“When I had to leave Paris in 1941, I gave Bartosch up for lost. The occupation of the Sudentenland had made him a German. The Nazis were aware that Bartosch had refused their passport, that during his Viennese period he had worked on films on Thomas Masaryk’s theses, and that he had begun an anti-Nazi film as propaganda against Hitler (1938). [Physically] lame as he was, not knowing how to speak French, he was far too distinctive and vulnerable to escape being quickly spotted.

When I saw him again in 1947 on the Boulevard St. Germain, and when I greeted him in German, with my Russian accent, he answered me in French: ‘Now I don’t spik Cherman anymore, I spik Franch.’ I asked about his film. ‘When they came to look for me,’ he told me, ‘they didn’t find me, but they found my film and they destroyed it.’

He planned to make a third film, a film still more grandiose, on the Cosmos. During the twenty last years of his life, he set about putting together all the details of this new film, whose secret he carried to his grave, November 13, 1968. . . . The destruction of the second film had been too hard a blow, even for Bartosch’s will of iron. He never complained about it, but I think that for the rest of his life he merely played with the idea of resuming his creative film work, while doubting his power to bring back to life what the war had crushed.”

One final note: in searching for an online version of Bartosch’s film, I came across Short Animated World, an excellent website that links many online versions of the titles chosen for Annecy Festival’s 2006 “100 Films for a Century of Animation” created by a worldwide poll of thirty specialists. Some of the links have been removed, but most of them remain, and are well-worth clicking through. The Idea comes in at ninth place. As you might expect, the films get less canonical the further down the list they appear, but most are still worth your time. The links tend to be unsubtitled versions of the films, but in many cases this is only a minor hurdle.

Among my personal (and available) favorites:

004 Crac! (Frederic Back)

005 The Man Who Planted Trees (Frederic Back)

006 Tale of Tales (Yuri Norstein)

008 A Color Box (Len Lye)

010 The Street (Caroline Leaf)

018 Tango (Zbigniew Rybczynski)

020 Begone Dull Care (Norman McLaren)

023 Father and Daughter (Michael Dudok de Wit)

025 The Hand (Jiri Trnka)

027 The Nose (Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker)

031 The Cameraman’s Revenge (Ladislaw Starewicz)

036 Composition in Blue (Oskar Fischinger)

041 Free Radicals (Len Lye)

042 The Ride to the Abyss (Georges Schwizgebel)

044 Franz Kafka (Piotr Dumala) . . . although I definitely prefer Dumala’s Crime and Punishment

046 Two Sisters (Caroline Leaf)

048 Balance (Christoph and Wolfgang Lauenstein)

049 Hedgehog in the Fog (Yuri Norstein)

050 When the Day Breaks (Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis)

051 Rooty toot toot (John Hubley)

054 Frank Film (Frank Mouris)

057 Mindscape (Jacques Drouin)

058 Jumping (Osamu Tezuka)

060 The Wrong Trousers (Nick Park)

063 Fast Film (Virgil Widrich)

066 Ryan (Chris Landreth)

070 Mt. Head (Koji Yamamura)

073 The Sinking of the Lousitania (Winsor McCay) . . . in spite of its flagrant warmongering

. . . the Kentridge and Borowczyk films should be seen in better quality . . .

Share Article

Share Article  Comics,

Comics,  Doug Cummings,

Doug Cummings,  Film

Film