The Julie Project

Thursday, February 3, 2011 at 11:38AM

Thursday, February 3, 2011 at 11:38AM Art is powerful when it imitates life - or stands witness to it, like documentary photographer Darcy Padilla does with her art/life projects.

In The Julie Project, Padilla followed her subject, Julie, off and on from 1993 (when Julie was 18) to Julie’s death in 2010 from AIDS. Padilla says,

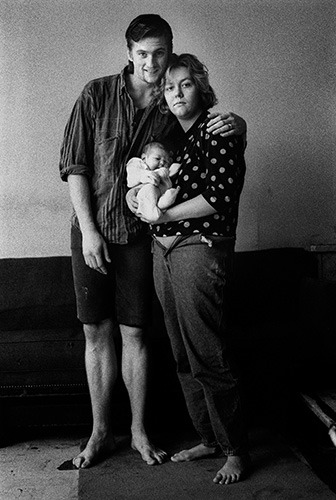

I first met Julie on February 28, 1993. Julie, 18, stood

in the lobby of the Ambassador Hotel, barefoot, pants

unzipped, and an 8 day-old infant in her arms. She lived

in San Francisco’s SRO district, a neighborhood of soup

kitchens and cheap rooms. Her room was piled with clothes,

overfull ashtrays and trash. She lived with Jack, father

of her first baby Rachael, and who had given her AIDS.

She left him months later to stop using drugs.

…

For the last 18 years I have photographed Julie Baird’s

complex story of multiple homes, AIDS, drug abuse,

abusive relationships, poverty, births, deaths, loss

and reunion. Following Julie from the backstreets of

San Francisco to the backwoods of Alaska.

When you look at the photos of someone’s life and death over 18 years, it’s compelling and powerful and voyeuristic all at once - in this case, like watching a train wreck and being deeply disturbed and finding yourself unable to look away. Is it exploitative? Do I think it’s exploitative because it’s disturbing, and disturbing things in life should be kept private? Why did Julie say yes to being photographed in the first place?

Julie at the age of 18, in 1993: (photo by Darcy Padilla)

Julie, nearing the end of her life at the age of 36, in 2010 - the photos get a lot worse shortly after: (photo by Darcy Padilla)

In the end, The Julie Project is art that stays with you and challenges you, which is the old version of what art was supposed to do. At the same time, talking about Julie’s life and death as an art project also feels wrong somehow, like this person who lived a tragic life of poverty, drugs, abuse, and AIDS has been reduced to something we can put up on the wall (or the web) and point at. And I did it too.

And yet, if we didn’t capture it and know about it, it would be easier for us to take comfort in the idea that that kind of life doesn’t exist. I’m not sure what to think.

UPDATE: The Julie Project is sparking lots of thoughts - here's what over 80 people had to say about it on Metafilter.

Art,

Art,  FS Michaels,

FS Michaels,  Photography

Photography

Reader Comments (8)

After not being able to tear myself away from that site until I'd read and seen every last thing, I really hope we can start a conversation about this in the comments here.

And Flora, you write: "...The Julie Project is art that stays with you and challenges you, which is the old version of what art was supposed to do." I'd like to hear about your take on the new version of what art is supposed to do.

Hey Rene, the new version of art is art that appeals to the market, meaning people will want to buy it - and art that's challenging often makes us uncomfortable, so we don't want to buy it. But I can't imagine this art is meant to be bought and hung on your wall anyway - so its success is maybe determined by how much it travels and what kind of exposure it gets. And then I wonder if it's successful because of its shock value? Because the project is shocking. (Here I'm already talking about this person who lived and died on camera as a project. And then again it's called The Julie Project.) And I had the same reaction you did to the site - I looked at every photo and read every word. What did you think, you artist you?

I haven't been able to stop thinking about this since Kate at Sweet Salty tweeted the link to it the other night. I found it deeply moving and, whilst almost unbearable to witness, has affected me profoundly. I will remember some of those photos for the rest of my life. Isn't that the effect art should have on someone?

I didn't think it was exploitative, in the same way I don't think war photography is.

That kind of life does exist and I think it helps to know about it.

I think that with something like this, there's no way to really sit with the work and come out changed, but it's a dirty process. No way to come out of it unsullied to some extent either. I guess that's what good art will do (clearly I ascribe to the old idea of what art is, F.)

I do wonder how a model release signed by a young, sick, hungry woman struggling with a cocktail of post-pregnancy hormones (and who knows what else) can be considered informed consent. But clearly Julie herself kept the relationship alive over many years, and Darcy seems to have been a positive force in her life and continues to be an advocate for her in death. The storytelling is harsh because it has to be, there's no other honest way. However, the voice used is neutral. No flourishes, at least that's how it feels to me. I respect that.

In the end the thing I most feel is compassion. This could be me. I could be Julie.

And this is work I could never make.

Uh, that should read "here's no way to really sit with the work and NOT come out changed".

Both sides now from Susan Sontag:

"To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder - a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time."

— Susan Sontag (On Photography)

"Certain photographs--emblems of suffering--such as the snapshot of the little boy in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943, his hands raised, being herded to the transport to a death camp--can be used as memento mori, as objects of contemplation to deepen one's sense of reality; as secular icons, if you will. But that would seem to demand the equivalent of a sacred or meditative space in which to look at them. Space reserved for being serious is hard to come by in modern society, whose chief model of a public space is the mega-store (which may also be an airport or a museum).

-Susan Sontag (Regarding the Pain of Others)

I viewed the images & read the story about an hour ago & I'm still processing.....mostly emotions but also opinions.

I appreciate the commentary so far.

I'm not really thinking about Julie either as "art" or a "project" right now. I agree with Deer Baby who said "That kind of life does exist and I think it helps to know about it"...but I'm not sure if the knowledge will make me more compassionate, though I hope it does.

Yes, I was deeply moved. It challenges me and I think it will stay with me. Thank you, F.

Damn. That phone call...

This is an incredibly powerful testament to a life. Darcy handled it with incredible care, humility, and humanity and you're right, Rene - there's no way to view that and not be impacted. It does seem that there was a real relationship between Darcy and Julie, one that does not strike me as exploitative at all. This is the sort of documentary of life in our society that we need to see more of. It puts me in mind of the work the gov't paid travelling photographers to do during the great depression, where they travelled through the fruit picking camps and shanty towns documenting the people and their lives. Incredibly powerful stuff and an important part of making an honest assessment of our society.